According to the description of Leonardo Torriani in “Descrizione e Storia del Regno delle Isole Canarie” (1588) the island of Gran Canaria in the past it was so fertile and abundant of goods that it was enough to sustain almost sixty thousand souls in such a small space of land, without any help from another place.

The population was so proud and cunning that in many military things, despite of their rusticity, they can be compared with noble nations.

It wasn’t the first time that the Canary Islands appear on a book, as I already wrote in this article: since the Roman Age many expeditions were taken on these lands, to discover and conquer new colonies. In the books of Plinio il Vecchio (Plinio the Elder, 23AD – 79AD) it’s written how the expeditions commanded by Juba II contributed to create the new map of the world. The etymological origin of the name Gran Canaria is explained by Plinio for the big amount of dogs (Canis in latin language) that lived on the island; but other linguistic and historical studies indicate the origin as a modulation of the name Canarii, a Berber tribe that was living in these places at that epoca. The studies are still on course…

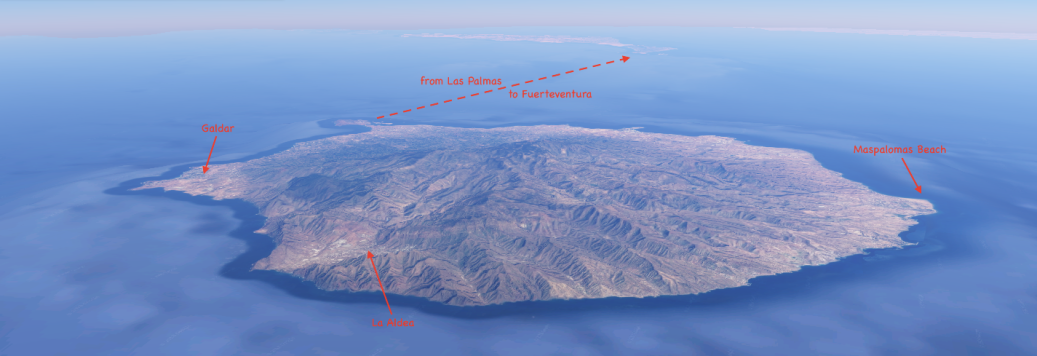

The name Canaria was considered the same for all the seven islands until the XV century, when finally it was explained by Enrique III in his Chronicles why the adjective Gran in front of the name (“Gran” means “big or great” depending by the interpretation). Writing about the Normans campaigns on the islands and the courage of the population in defeating the mother land, he wrote: “…and from now on I command that this, my island of Canaria, be called Grande”. In the pre-Hispanic period it was organized by a system of governing different from the other islands, and based on Guanartemato and Faycanato, replacing the council of chiefs of tribes. Here’s a little list: Gáldar, Telde, Agüimes, Tejeda, Aquexata, Agaete, Tamaraceite, Artebirgo, Artiacar and Arucas. With rare exceptions, these places correspond to the current names of the towns.

Nowadays, there are various studies that shows how the human settlements were possible on the island: Celso Martin de Guzman in his work “Las culturas prehistóricas de Gran Canaria“ (1984) give us informations about the residential areas, and also in further studies it was documented the presence of different communities: agricultural settlements of coastline, same settlements but on the internal valleys, communities of the forest and shepherds communities. When the Spanish conquered the island, they suddenly dedicated lots of effort to share the island and create a system to irrigate the plants in the most quick and convenient way, using the technology at disposition of the Crown. Finally they obtained a distribution module to irrigate lands that was called fanega. With these rules, the royal delegates distributed the lands destined for irrigation and agriculture between the conquerors and new settlers, waiting to their rank and participation in the process of conquest and colonization.

It was also introduced a code of rules to preserve the nature of palm trees, cardones, incense, escobones, holy wood, reeds, thorns and balos that included the prohibition of cutting palms, pine groves, etc.

With this system, Pedro de Vera nominated a commission of nine deputies that he delegates to do the different repartimientos, dividing the island in three districts: Gáldar, from the ravine of Aumastel (later Azuaje) to the territories of La Aldea; Las Palmas, from the Aumastel to the limit of Telde; and the same Telde, that included all the rest of the island with the exception of the South-West that was counted as a particular property of the Spanish Kings. When these uncultivated lands and mountains were requested, they were assigned as property to the Cabildo, that distributed them according to the and population needs.

To consolidate the conquest, Gran Canaria was organized with the most representative institutions in the region: the Governor with its twelve regidores and the Bishopric of the Canarian Church (both in 1485), the Tribunal del Santo Oficio for the Inquisition’s priests (in 1501), the Real Audiencia de Canarias (in 1526) and the Captain General (in 1589). From the first moment, the Cabildo General (General Council) became the maximum representation of the municipal power, the model to follow for a better implementation of the Castilian administrative system in the islands of the archipelago.

The first legal dispositions appear in 1494 and they concern the management and organization of the Canarian territory, the system of weights and measures, as well as the monetary value and the economic exploitation strategies.

In the XVI century finally the colons begin their settlements in the island, thanks also to the financing obtained by the city of Genova, Italy. In a lot of cases, they built their new towns up on the same pre-hispanic settlements: this fact modified or destroyed a lot of informations that nowadays scientists and archeologists are still searching on the territory. As you can imagine, after the new houses the population asked for more services and so they were build churches, hermitages and palaces.

After this economic boom Gran Canaria lived almost two centuries of crisis for the commerce, for the strong competition with South America in the production of sugar. It was only after this epoca that the new vineyards, the cane fields, the grocery trade and the massive tourism became all together the new economic strength of the island.

The administrative reforms promoted by Carlos III in the XVIII century introduced in the local governments a unique electoral process for the election: it’s a new time of prosperity for Gran Canaria, with a clear increasing of the population and the growing of new independent town halls. San Mateo and Valsequillo were the first ones, in the first decade of XIX century; later, it happened also to Mogán, Santa Lucía de Tirajana and Ingenio, in the second decade, and finally, in the fourth decade, Valleseco.

At the current day, it’s interesting to notice how the old names of plants, places, families or people became part of the common language of the Canary Islands, as well as in the island of La Gomera a simple whistle can be considered a entire language.

So what can I write more about the history of Gran Canaria? I believe the only way to feel really fascinated by this island is to come and see with your own eyes… it’s what I did eight years ago and I’m still here. It can’t be so bad… 😉

3 thoughts on “The Origins of Gran Canaria”